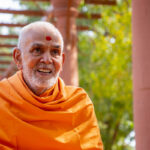

Imagine a desert, barren and dry—a landscape of spiritual thirst. Now, picture a perfect rose blossoming in its midst. This, in essence, was the life of Nishkulanand Swami. In an age of crumbling kingdoms, famine, and a desperate scramble for power and security, he emerged as a luminary of divine paradoxes. He was a man who embodied extremes: profound detachment fused with deepest devotion, staggering genius born from apparent illiteracy, and radiant contentment found within a life of deliberate, comfortless austerity.

His story is not just a historical account of one of Bhagwan Swaminarayan’s 500 paramhansas; it is a living blueprint for the modern seeker. In a world that equates achievement with accumulation and happiness with comfort, Nishkulanand Swami’s life offers a revolutionary counter-narrative: true fulfillment is found not in what we gather, but in what we gracefully give up for God.

From Lalji Suthar to Vairagya Murti: The Making of a Detached Devotee

Nishkulanand Swami’s journey begins not in a palace of learning, but in the humble village of Shekhpat. Born as Lalji Suthar in 1766, he was by worldly standards, illiterate—a carpenter by trade with no formal education. Yet, the seeds of greatness were sown not in classrooms, but in nightly goshtis with the young Muktanand Swami (later Gunatitanand Swami). Together, they would walk miles after a full day’s work, fueled solely by utsah to discuss Bhagwan’s glory. This early satsang was the crucible where his spiritual mettle was formed.

The Desert Crucible: A Journey of Letting Go

His transformation was catalyzed by a single, transformative journey with Shriji Maharaj from Shekhpat to Kutch. Acting as a guide, Lalji Suthar meticulously prepared—packing food, water, and even hiding coins in his shoes for security. One by one, Maharaj asked him to give it all away: food to a beggar, coins to thieves, water to a thirsty sadhu. It was a masterful dismantling of his ego and dependency on material planning.

Key Quote:

“Maharaj wasn’t taking away the food and the water… subtly, he’s taking away his ego, his comfort, his desire for all of the material things.”

The climax arrived in the desert’s heart. With no water left, Maharaj instructed him to dig, revealing sweet water—a miracle that turned salty the moment doubt arose. This lesson was clear: the only true refuge and sustenance is God Himself.

The Ultimate Test: Vairagya at the In-Laws’ Door

The final test of his detachment was even more personal. In Adhoi, Maharaj, now thirsty and hungry, asked him to beg for food. The problem? It was his in-laws’ village. Disguised as a sadhu with a shaved head, he knocked on their door. When his family saw him, they called his wife and children, hoping family ties would pull him back. His response was the firm resolve of a true vairagi:

Key Quote:

“Look, Shriji Maharaj is here in the village. He’s hungry. I’ve come to beg for food… But don’t talk to me about coming back into sansar.”

He returned with food for Maharaj, having passed the ultimate test. From this steadfastness, he was named Nishkulanand—one who finds joy (anand) in renunciation (nishkula). His detachment was so potent it became infectious, inspiring his own sons, Madhavji and another, to embrace sannyasa and become Govindanand Swami and another sadhu.

The Illiterate Genius: Where Divine Grace Meets Profound Wisdom

Here lies the first breathtaking paradox. Nishkulanand Swami, the carpenter with no formal schooling, became one of the most prolific and profound literary figures in the Sampraday. Upon his initiation, Shriji Maharaj bestowed a divine blessing: “Whatever you write now will become poetry.” This was not mere metaphor.

A Prolific Literary Legacy

He authored 23 granths, including the monumental Bhakta Chintamani, a scripture detailing Shriji Maharaj’s life, leelas, and the ideals of a devotee. His works like Yamadanda, Vachanamrit Vidi, and Purushottam Prakash covered vast ground—from the sufferings of hell to the rules of conduct and the purpose of God’s incarnation. His Chosath Padi (64 verses), a fearless guide to discerning true and false sadhus, was so forthright it was burned multiple times by those it exposed.

Key Quote:

“I’m telling you the bitter truth… just as a doctor he has to give a bitter medicine to the patient so that his disease will go.”

Master of Metaphor and Human Psychology

His genius lay in his ability to translate complex spiritual truths into stunning, relatable metaphors. He didn’t just use conventional imagery; he crafted profound analogies from everyday life:

- He compared the ocean, which shelters all but casts out the dead, to Satsang, which accepts all but rejects ungodly traits.

- He described his eagerness to narrate Maharaj’s exploits as a thirsty man finally finding a pot of nectar (amrut).

- In Manganjan, he masterfully depicted the internal battlefield of the mind, showing a deep understanding of human psychology that resonates with Shriji Maharaj’s own teachings in the Vachanamrut.

This intellectual and creative explosion defies worldly logic. The source was twofold: the krupa of Shriji Maharaj and the samagam of the Satpurush, Gunatitanand Swami, whose association had rooted the majesty of the Sant in his heart from the very beginning.

Detached Yet Devoted: The Sacred Paradox of a Sadhu’s Heart

The world often sees detachment (vairagya) and devotion (bhakti) as opposites—one cold and dry, the other warm and emotional. Nishkulanand Swami’s life synthesizes them into a harmonious whole. His vairagya was not a dry, weary rejection of the world, but a vibrant, positive attraction to Bhagwan.

Vairagya as the Foundation for Agna

His detachment was the bedrock of his obedience. Once, when Maharaj instructed him to address a female assembly, he respectfully declined, citing the agnas of brahmacharya. His vairagya empowered him to follow the higher principle, even when tested by a divine command. It was vairagya rooted in bhakti, not in spite of it.

Running from Comfort, Running Towards God

He actively cultivated a comfortless life to protect his devotion. In Vadodara, seeing pots of rich milk sweets (laddus) prepared for a festival, he grew anxious, feeling such luxury was a threat to his simple existence. Understanding his intensity, Gopalanand Swami had the sweets removed. Nishkulanand Swami avoided cities and chose to live in simple Dholera, eating only rotlo and chaas (bread and buttermilk) even in old age, when he could have requested more.

His most telling refusal was of power. When Maharaj proposed making him the Mahant of the Gadhada mandir, he quietly fled to a nearby village. Upon his return, he explained:

Key Quote:

“What if a huge weight was to fall on a tiny little mouse? Then that mouse would get crushed… If I were to be given the whole administration… then I would degenerate spiritually.”

In an era—and indeed, in our own—obsessed with climbing ladders and claiming status, he sought only the “Mahanti of being in Maharaj’s heart.”

Comfortless Yet Content: The Art of Divine Fulfillment

The final paradox is perhaps the most liberating for the modern devotee. Nishkulanand Swami embraced a life of minimal physical comfort, yet his writings overflow with the language of supreme contentment and soul-deep joy. He had discovered that prapati (attainment of God) is the only wealth that matters.

The Disgust for Worldly Illusions

In a powerful kirtan, he expresses his complete disillusionment with worldly pleasures (vishays):

Key Quote:

“Mune saapanen gamde sansar…” – “I do not like sansar even in my dreams.”

He compares the soul’s attitude after realizing God to vomit—once expelled, one feels utter disgust at the thought of re-consuming it. He asks: if a lion is before you, do you think of pizza? When death (the lion of worldly existence) is clear, all vishays lose their allure.

The Joy of the True Wealth

Yet, this vairagya was not emptiness. It was filled with the ecstasy of divine attainment. He chastises the mindset of spiritual poverty:

“Shiddhane reyere kangal…

Jare mario maha moto mala re santur.”

(Why do you consider yourself a pauper, O Saint… when you have attained this immense, unfathomable treasure?)

He illustrates this with the parable of the beggar-turned-queen who, despite having royal feasts, only found joy in scavenging for hidden scraps. His point is piercing: we, who have attained the King of kings, still scavenge for petty, worldly pleasures. True anand is in reveling in the prapati of Bhagwan and Sant.

His final words in the Bhakta Chintamani, written as his eyesight failed, are a testament to this lifelong, contented focus:

“If I have life in me, my tongue, my body, my mind will talk about Sahajanand Swami’s glory… I won’t hear, see, or touch anything else.”

Nishkulanand Swami’s life is a diamond covered in the dust of simplicity, waiting to be discovered by each generation. He teaches us that:

- True genius is not a product of degrees but of divine grace and Sant-krupa.

- Real detachment is not about running from the world, but running towards God with such speed that everything else falls away.

- Lasting contentment is found not in accumulating comforts, but in cherishing the supreme comfort of God’s presence.

In an age of infinite distractions and complex anxieties, his paradoxes offer a profound simplification. The path to peace is not about adding more to our lives, but about having the clarity to let go of everything but the One. He remains, as Mahant Swami Maharaj reminds us through the kirtan “Mano Mari Che Moti Vaat,” the eternal guardian of that precious, priceless gem—the prapati of Akshar-Purushottam. Our quest is to polish that diamond within our own hearts.

Follow our socials: https://linktr.ee/thesatsanglife

Podcast Location: BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, Brisbane: https://www.baps.org/Global-Network/Asia-Pacific/Brisbane.aspx

+ There are no comments

Add yours